What and why

Governments in Asia and the Pacific should agree on national visions for social protection that make medium and long-term ambitions clear to all. Without a clear vision across government ministries, key actors and the public, social protection systems risk becoming fragmented and insufficiently funded, with significant coverage gaps and too low benefit levels as a result. At the regional level, ESCAP member States adopted the ESCAP Action Plan to Strengthen Regional Cooperation on Social Protection in Asia and the Pacific, which serves as a shared vision and platform for the region to achieve inclusive, comprehensive and adequate social protection for all.

How

When creating a vision for social protection, the process is vital. From the outset, it is essential to seize the process as an opportunity to generate public support and political will. With clear incentives and a shared understanding of the impacts of social protection, governments will be better positioned to assess what is in place and then agree on a way forward. Responsibility for this process should be located at the Prime Minister’s or Coordination Ministry’s Office and consult representation from diverse groups to ensure that needs and views are reflected in the vision.

Policymakers have long viewed social protection as a policy tool for poverty reduction. Reducing its utility to this one important function will leave governments short-handed when it comes to the larger purpose and impact of social protection, including the broad public support it can achieve. Policymakers can most effectively generate public support for social protection when it is upheld as a human right for all (Milestone 2) and designed as an individual entitlement that everyone can access and benefit from throughout their lives (Milestone 3).

Political will can be generated through a shared understanding of the benefits social protection has on society through its potential to achieve diverse development goals. Unleashing this potential will require allies across government, academia and civil society to understand social protection as:

FIGURE 1‑1 Virtuous circle of investing in good quality public services, leading to a strong social contract

- An indispensable key to unlock the many benefits of a strong social contract. When delivered in a fair and equitable manner, social protection can make major contributions to strengthening the social contract between citizens and the State, which is essential for State-building. When women and men receive tangible support from their government, they are more likely to trust their government. They are also more likely to fulfill mutual obligations and contribute back to their governments through, for example, taxes. The equitable redistribution of national wealth also contributes to building solidarity within communities and more peaceful societies. This, in turn, builds a State that is trusted and better positioned to provide quality public services (see Figure 1-1).

- A pillar for equitable economic growth and decent work creation. Inclusive social protection supports access to nutrition, education and healthcare for all throughout people’s lives. It is an investment in human capital and is essential for building a skilled and productive labour force that is competitive in a globalized economy. Social protection also stimulates demand and consumption, creating markets for small enterprises, with a multiplier effect for cash entering local economies. It also provides women and men with a foundation to invest in new sources of income and contributes to greater economic stability that attracts markets for local and foreign investors. Furthermore, contributory schemes boost decent work opportunities.

- A strong foundation to respond to different shocks. Through directly supporting aggregate demand, social protection acts as an economic stabilizer, cushioning the impact of various shocks. Having inclusive social protection systems in place prior to a crisis leaves governments with more options and better prepared to respond quickly by scaling up what is already in place. It also helps people to recover faster from a shock by protecting them from losing productive assets or falling into negative coping mechanisms.

- An automatic stabilizer to life disruptions. When comprehensive contributory and non-contributory schemes are in place, they automatically provide income or in-kind support to individuals that suddenly fall sick, have an injury or disability, lose a job, or simply have a child or become old. Schemes for these and other life situations protect households from the insecurity and vulnerability that could otherwise force families to sell assets or take children out of school. By providing a predictable and regular source of income, social protection also allows households and individuals to take more risks to grow and expand their livelihoods.

- An effective tool to reduce poverty and promote social inclusion and gender equality. When inclusive in design, social protection reduces poverty by putting cash directly in people’s pockets. When provided as an entitlement on an inclusive basis, social protection promotes social cohesion and the inclusion and empowerment of women, single parents, as well as minorities and people who face diverse and persistent forms of exclusion or discrimination, including migrants, ethnic minorities, persons with disabilities, displaced persons and refugees.

With a shared understanding of the benefits that social protection can bring to society to achieve diverse Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), governments will be in a position to more consultatively and comprehensively identify challenges that address and articulate new policies.

Address key challenges. This requires governments to review national development plans and progress toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Having a clear understanding of social protection as a multifaceted policy tool requires policymakers to look broadly at the types of challenges social protection can help address, beyond poverty reduction. As such, governments should engage in broad consultation with relevant line ministries and civil society to take stock of the status of the identified challenges and how these interact with the unique needs and circumstances of people.

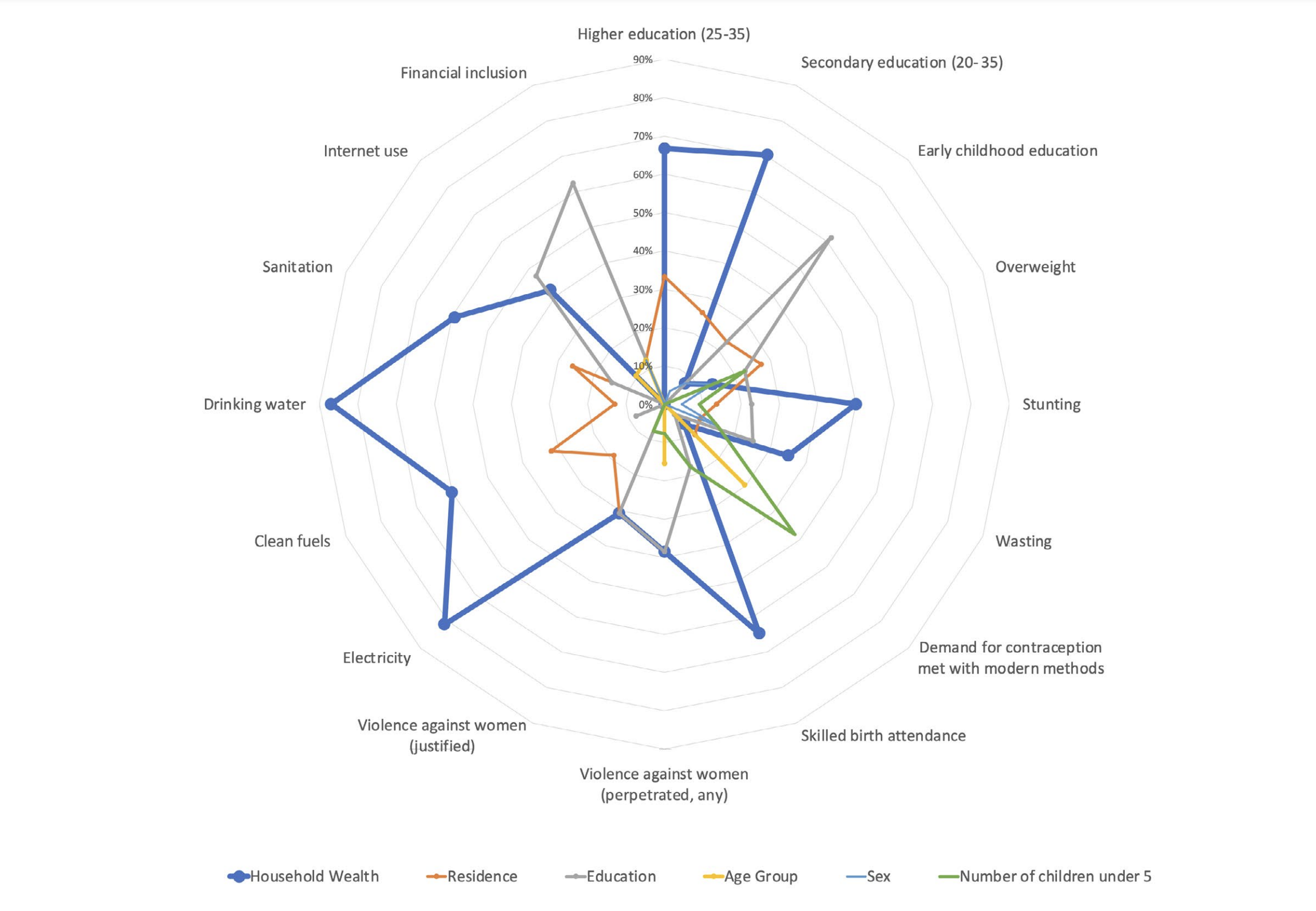

Identify ways to close social protection gaps. This requires governments to identify population groups being left behind and why. ESCAP analysis uses data from Demographic Household Surveys (DHS) and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) to identify which groups are left furthest behind with regard to accessing a range of basic opportunities outlined in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Data from 27 countries reveal that household wealth is either the most, or one of the most, important circumstance among groups left furthest behind in almost all opportunities (see Figure 1-2). Though household wealth, a proxy for income, is an overshadowing circumstance, the data also highlight the interlinkages with other circumstances across the life cycle, such as educational attainment, or the number of children in a household. This shows the importance social protection can play for a wider range of basic services and opportunities, in addition to normal income-related challenges. Interventions therefore should not focus on poverty alleviation alone, but on addressing vulnerability across the life cycle. Governments should also identify inclusion and exclusion errors in existing benefit schemes to gauge their effectiveness in providing adequate support, while responding to international human rights obligations (Milestone 2).

Once the above challenges and gaps have been identified, governments must reach agreements on prioritized interventions and a vision to incrementally build sustainable social protection systems. This vision should be integrated into national development strategies and social protection sectoral plans across government, to ensure policy coherence and coordination.

FIGURE 1‑2 Identifying dominant circumstances of those left furthest behind in accessing 16 key opportunities

Many countries tend to first focus on providing regular, predictable, and reliable entitlements to older persons and persons with disabilities following the life cycle approach outlined in the International Labour Organization (ILO) Social Protection Floors Recommendation, 2012 (No. 202). Building a multi-tiered social protection system with a mix of contributory and non-contributory schemes often increases coverage, benefit adequacy and sustainable financing (Milestone 4).

Ensuring accountability for the shared vision requires governments to document phased actions in measurable steps that can be monitored over time. These steps should be linked to achievable national targets that are based on country contexts within the indicator framework of SDG 1.3, with a focus on achieving full social protection coverage of the entire population by 2030. For this purpose, ESCAP member States adopted this ambition through Action (h) of the ESCAP Action Plan to Strengthen Regional Cooperation on Social Protection in Asia and the Pacific.